- Home

- Your Diabetic Information Center

- Glycemic index chart for everyday foods

Understanding the glycemic index chart for diabetics for everyday foods

The glycemic index (GI) chart is a practical tool that shows how different carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood sugar levels after eating. It ranks foods based on how quickly they are digested and absorbed and how rapidly they raise glucose in the bloodstream compared to pure glucose.

Carbohydrates that break down quickly during digestion cause a faster and higher rise in blood sugar and are classified as high-GI carbohydrates. In contrast, low-GI carbohydrates are digested more slowly, leading to a gradual increase in blood glucose.

Understanding the glycemic index helps people make informed food choices, support stable energy levels, and improve blood sugar control, especially for individuals managing diabetes or insulin resistance.

What is the glycemic index, and why does it matter?

The glycemic index (GI) is a system that ranks carbohydrate-containing foods based on how quickly and how much they raise blood sugar levels after being eaten.

Foods with a high GI are digested rapidly, causing sharp spikes in blood glucose, while low-GI foods are absorbed more slowly and lead to steadier levels.

The glycemic index matters because it helps people make smarter food choices, improve blood sugar control, maintain stable energy levels, and reduce the risk of insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and long-term metabolic complications.

When you look at a glycemic index (GI) chart, you can see that low-GI foods release glucose more slowly and steadily into the bloodstream. This gradual absorption helps maintain stable blood sugar levels. In contrast, high-GI foods are digested quickly and can cause rapid rises in blood glucose.

High-GI foods are not always negative. They can be useful after intense physical activity, when the body needs to replenish energy stores quickly, or in cases of hypoglycemia, where blood sugar levels drop suddenly and need to be corrected promptly.

Studies using animal models have demonstrated that diets rich in high-GI carbohydrates correlate with a heightened risk of obesity. In human studies, however, the relationship is more complex. Factors such as fiber intake, food processing, palatability, portion size, and dietary adherence all influence metabolic outcomes, not GI alone.

The glycemic effect of a food depends on several important factors. One key factor is the type of starch it contains—specifically the ratio of amylose to amylopectin. Foods higher in amylose are digested more slowly and tend to have a lower GI.

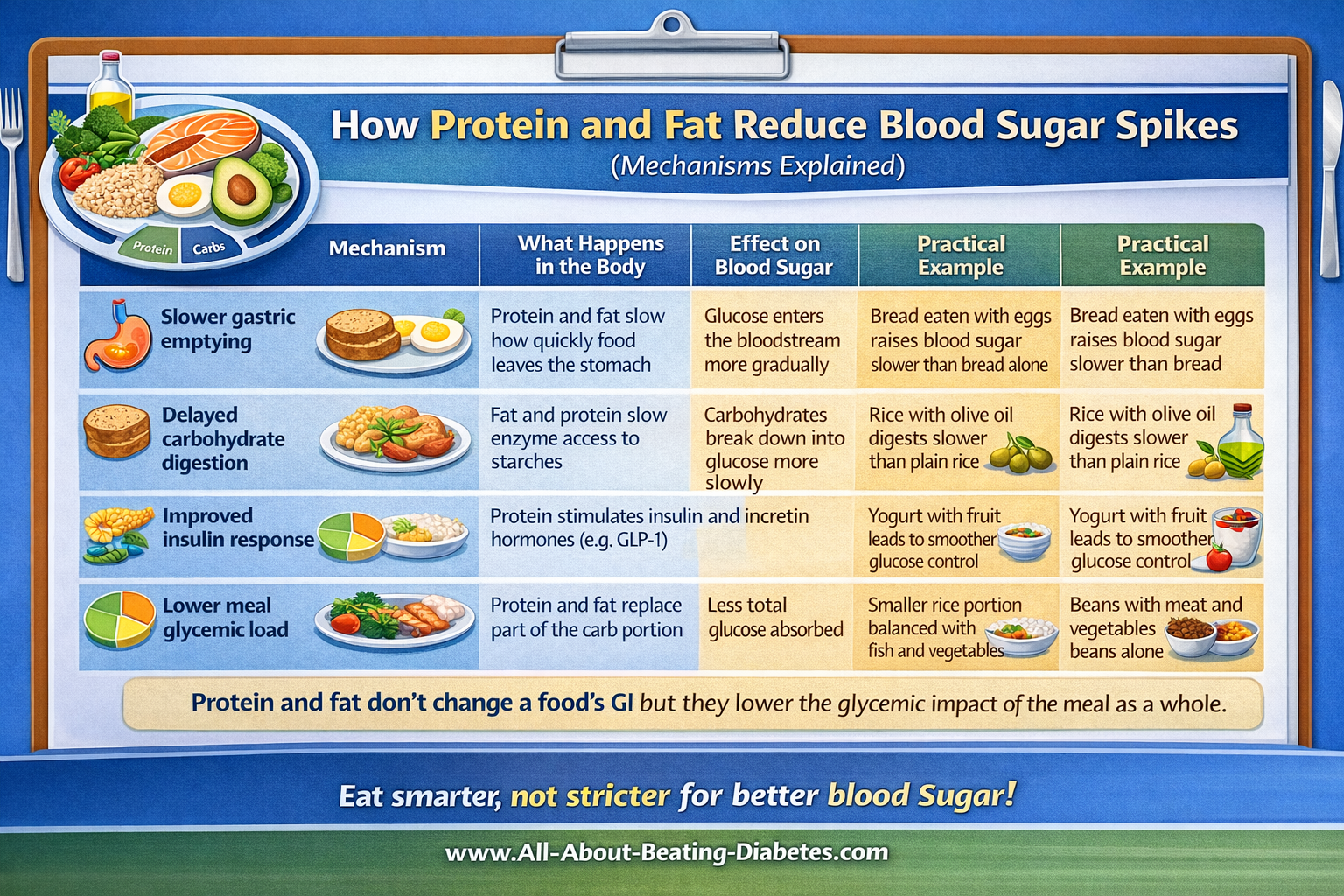

Other influencing factors include the physical structure of starch, the presence of protein and fat, and organic acids in a meal. For example, adding vinegar or other acidic components can lower the glycemic response to a meal by slowing digestion.

Soluble dietary fiber also plays a major role. Fiber slows gastric emptying, meaning food stays longer in the stomach, which indirectly reduces the glycemic response. This feature is why unrefined, fiber-rich breads generally have a lower GI than white bread. However, some commercially produced brown breads are treated with enzymes that soften the structure, increasing starch availability and raising their GI despite their darker color.

Adding fat or oil to a meal—such as butter or olive oil on bread—does not change the GI value of the food itself, but it lowers the overall glycemic impact of the meal. Even so, white bread will still produce a higher blood glucose curve than whole-grain bread, regardless of added fats.

The glycemic index chart focuses on carbohydrate quality, but it is also important to consider glycemic load, which reflects both carbohydrate quality and quantity. Most fruits and vegetables contain relatively small amounts of carbohydrates per serving and therefore have both a low GI and a low glycemic load, making them excellent choices for people with diabetes.

Some foods, such as carrots, were once thought to have a high GI, but updated research shows they have a low glycemic impact and significant nutritional benefits. Potatoes and watermelon, however, tend to have higher GI values and should be consumed with attention to portion size and meal composition.

The Glycemic Index Symbol Program was developed to help consumers identify foods and beverages that meet standardized low-GI criteria. Products carrying this certification are tested according to international standards and must also meet nutritional requirements related to calories, fat, and salt content.

When meals are planned using GI principles, carbohydrates typically provide around 50% of total energy intake, consistent with balanced dietary guidelines. Used correctly, the glycemic index helps people maintain stable blood sugar levels without reducing total calorie intake, supporting both metabolic control and long-term health.

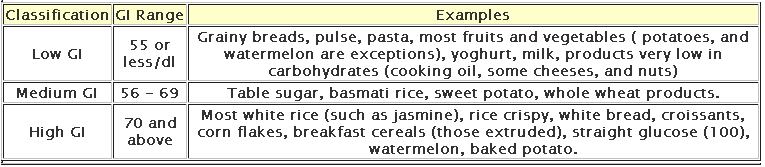

What do low, medium, and high GI values mean?

The glycemic index (GI) is divided into three categories that help explain how quickly carbohydrate-containing foods raise blood sugar levels.

- Low-GI foods, with a value of 55 or less, are digested slowly and cause a gradual rise in blood glucose, making them ideal for steady energy and blood sugar control.

- Medium-GI foods, with values between 56 and 69, lead to a moderate increase in blood sugar.

- High-GI foods, with a value of 70 or higher, are digested rapidly and can cause sharp blood sugar spikes.

| Glycemic Index (GI) Range | Category | What It Means for Blood Sugar | Educational Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–55 | Low GI | Causes a slow and gradual rise in blood glucose | Best choice for stable energy, improved blood sugar control, and diabetes management |

| 56–69 | Medium GI | Leads to a moderate increase in blood glucose | Can be included in balanced meals, especially when paired with fiber, protein, or healthy fats |

| 70+ | High GI | Causes a rapid spike in blood glucose levels | Should be limited, particularly for people with diabetes or insulin resistance |

Understanding these ranges helps people choose carbohydrates more wisely, especially when managing diabetes or insulin resistance.

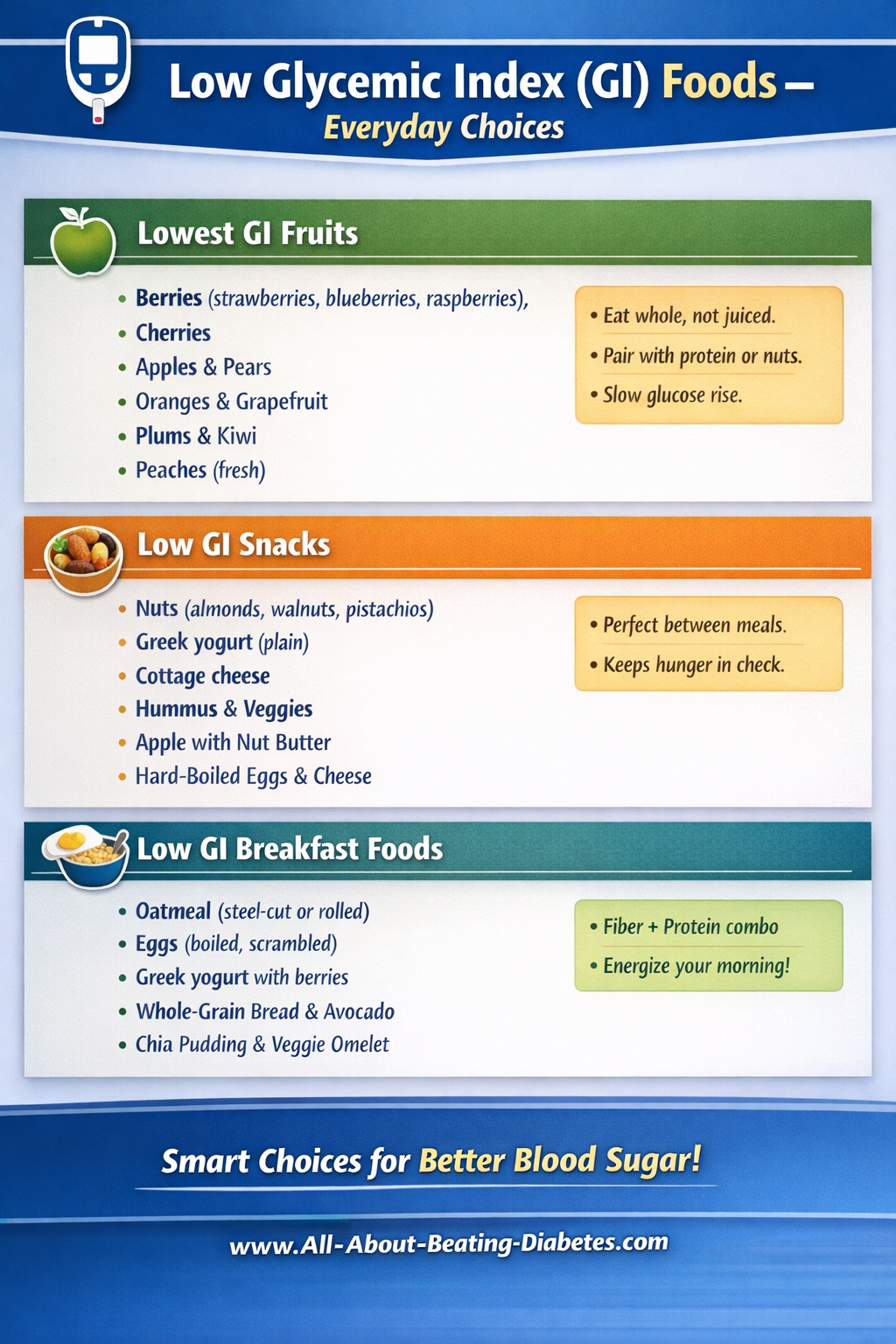

Which foods have the lowest glycemic index?

Low-GI eating is about food choices and combinations, not restriction. These foods work best when eaten in normal portions and combined with fiber, protein, or healthy fats.

The lowest GI fruits (fresh, whole) raise blood sugar slowly when eaten whole. That's why we do recommend eating fruit whole, not juiced, and pairing it with protein if possible.

Low-GI snacks (simple & filling) are ideal between meals to avoid glucose spikes.

Low GI breakfast foods (daily-friendly) help start the day with stable energy.

Why does the same food have different GI values?

The same food can have different glycemic index (GI) values because GI is strongly influenced by how a food is ripened, prepared, and processed. These factors change how quickly carbohydrates are broken down into glucose during digestion.

Ripeness matters. As fruits ripen, starches are converted into simple sugars. For example, an unripe (green) banana has a lower GI than a fully ripe banana because its carbohydrates are digested more slowly.

Cooking method matters. Cooking softens food structure and gelatinizes starch, making carbohydrates easier to digest. Raw carrots or al dente pasta have a lower GI than fully cooked carrots or overcooked pasta.

Physical form matters. Whole foods digest more slowly than processed forms. Whole apples have a lower GI than applesauce; boiled potatoes have a lower GI than mashed or instant potatoes because mashing breaks down fiber and increases surface area for digestion.

These examples show why food preparation education is essential. Small changes in ripeness, cooking time, or texture can significantly affect blood sugar response—often without changing the food itself.

Are low-GI foods always healthy?

Low–glycemic index (GI) foods are not automatically healthy, and relying on GI alone can be misleading from a medical perspective.

The glycemic index measures only the speed at which carbohydrates raise blood glucose levels. It does not account for a food’s caloric density, fat quality, added sugars, sodium content, or micronutrient value.

Certain foods such as chocolate, ice cream, or potato chips may have a lower GI because their high fat content slows gastric emptying and glucose absorption. However, these foods are often energy-dense, high in saturated or trans fats, and nutritionally poor, increasing the risk of weight gain, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease.

Clinical guidance emphasizes that healthy eating—particularly for people with diabetes—should integrate GI with glycemic load, portion size, fiber intake, overall dietary pattern, and individual glycemic response. Whole, minimally processed foods that are low-GI and nutrient-rich are preferred, whereas low-GI processed foods should be consumed sparingly.

Across major clinical organizations, the consensus is clear:

Glycemic index is a useful tool—but never a standalone measure of food health.

Best practice combines GI with portion control, glycemic load, nutrient quality, and individual glucose monitoring.

Can protein or fat lower the glycemic index of a meal?

Protein and fat do not change the GI of a food, but they lower the glycemic impact of the meal as a whole. This is why mixed meals cause fewer blood sugar spikes than carbohydrate-only meals.

What’s the difference between glycemic index and glycemic load?

Glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) are related but distinct concepts that help explain how carbohydrate-containing foods affect blood sugar levels.

The glycemic index measures how quickly a food raises blood glucose after it is eaten, compared with pure glucose. It focuses on the quality of carbohydrates and ranks foods as low, medium, or high GI based on the speed of their effect.

The glycemic load, on the other hand, considers both the speed of blood sugar rise and the amount of carbohydrates consumed in a typical portion. This makes GL a more practical, real-world measure. A food can have a high GI but a low GL if eaten in a small portion, while a low-GI food can still significantly raise blood sugar if eaten in large quantities.

For everyday decision-making—especially for people with diabetes—glycemic load often provides a clearer picture of a food’s true impact on blood glucose.

Are GI charts accurate for everyone?

Glycemic index charts are valuable educational tools, but they are not perfectly accurate for every individual. GI values are calculated under standardized laboratory conditions using average responses from healthy volunteers. In real life, however, blood sugar responses vary significantly from person to person.

Individual blood sugar responses

Each person’s glucose response is influenced by factors such as insulin sensitivity, gut microbiota, age, physical activity, stress, sleep quality, and medications. Two people can eat the same food and experience very different blood sugar rises. This phenomenon is especially true for people with diabetes or prediabetes.

Cultural and regional foods

Standard GI charts, often based on Western diets, do not adequately represent many traditional or regional foods. Preparation methods, ingredients, and combinations used in local cuisines can change the glycemic effect of a food substantially.

Differences between people

Portion size, meal composition, and timing all matter. A food’s GI does not account for how it is eaten in daily life.

Why personal monitoring matters

For these reasons, personal blood glucose monitoring and diabetes calculators are essential. They help translate general GI guidance into individualized, practical decisions—allowing people to understand how their own body responds and to manage blood sugar more safely and effectively.

GI charts guide education; personal data guides precision!

Should I rely only on the glycemic index chart?

The glycemic index (GI) chart is a beneficial educational guide, but it should not be used as a rulebook or the sole basis for food choices. GI explains how quickly carbohydrates raise blood sugar under standardized conditions, but it does not reflect how foods are eaten in real life or how individual bodies respond.

For balanced blood sugar management, several additional factors are essential:

Fiber content plays a major role in slowing digestion and glucose absorption. Foods rich in fiber often lead to more stable blood sugar responses, even if their GI is moderate.

Portion size directly affects blood sugar levels. A small portion of a higher-GI food may have less impact than a large portion of a low-GI food.

Overall nutrition matters. Healthy eating includes adequate protein, healthy fats, vitamins, minerals, and minimal processing—not just a favorable GI number.

Blood sugar tracking provides personal insight. Monitoring glucose levels before and after meals helps identify how specific foods and combinations affect your body.

In practice, the glycemic index should be used as a starting point, combined with mindful portions, balanced meals, and personal glucose monitoring for safer, more effective long-term blood sugar control.

Is glycemic index useful for people with type 2 diabetes?

Yes, the glycemic index (GI) is useful for people with type 2 diabetes, but it should be applied thoughtfully and flexibly, not rigidly. GI helps identify carbohydrates that raise blood sugar more slowly, which can reduce post-meal glucose spikes—an important goal in diabetes management.

However, people with diabetes do not need to eat only low-GI foods. A healthy diabetes diet is not about restriction but about balance. Medium- or even higher-GI foods can be included when portions are appropriate and meals are balanced with fiber, protein, and healthy fats. The overall pattern of eating matters more than individual GI values.

Regarding long-term control, research shows that diets emphasizing low-GI foods can contribute to improved HbA1c levels, especially when combined with portion control and overall nutritional quality. The benefit is modest but clinically meaningful when sustained over time.

Most importantly, GI should support—not replace—personal blood sugar monitoring. Individual responses vary, and people with type 2 diabetes benefit most when general GI guidance is combined with glucose tracking, lifestyle habits, and personalized medical advice.

Used correctly, the glycemic index is a supportive tool—one piece of a comprehensive, patient-centered diabetes care plan.

In the following table, you can find the glycemic index for the specific food you are interested in:

|

Written by Dr.Albana Greca Sejdini, Md, MMedSc Medically reviewed by Dr.Ruden Cakoni, MD, Endocrinologist |

Last reviewed 1/6/2026 |

Diabetes complications Questions or Problems? Get Help Here

This is the place where you can ask a question about any aspect of diabetes complications.

It's free and it's easy to do. Just fill in the form below, then click on "Submit Your Question".